By Ismail Royer

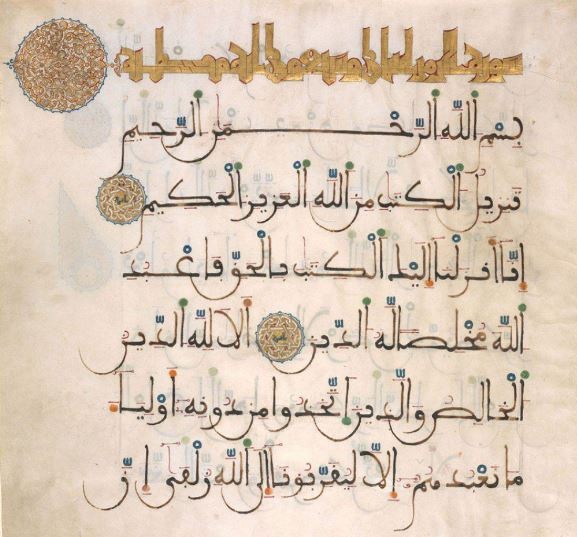

Allah says in Surah az-Zumar 39:63:

له مقاليد السماوات والأرض

To Him belong the keys of the heavens and the earth.

Ibn Katheer said this means:

أن أزمة الأمور بيده ، له الملك وله الحمد ، وهو على كل شيء قدير

That the control of all things is in the Hand of Allah, His is the dominion and to Him belongs all praise, and He is able to do all things.

In Arabic, the word translated here as “keys” is maqaaleed (مقاليد). The more common word for “keys” in Arabic is miftaah (pl. mafaatih), as in Surah al-An’am 6:59

عِندَهُۥ مَفَاتِحُ ٱلْغَيْبِ لَا يَعْلَمُهَآ إِلَّا هُوَ

And with Him are the keys of the unseen; none knows them except Him.

A few years ago my Quran teacher mentioned to me that the singular form of the word maqaaleed is iqleed (إقليد), which he said was an Arabized form of the Persian word kileed (کلید). This would make it one of the many Arabic words of foreign origin that were absorbed into classical Arabic prior to the Quran’s revelation.

My teacher’s comment stuck with me, because the word kileed sounds as if it were related to the Bosnian (i.e. Serbian or Croatian) word ključ, and possibly the English word “key.” I also thought it would be interesting to trace the path of one of the words of foreign origin in the Quran. And given that Allah chose every word of the Quran with wisdom and purpose, can we infer the wisdom in the choice of this word? Years later, with the benefit of more resources, I finally got around to looking deeper into the matter and setting down some of my research.

Iqleed in the Arabic of the Prophet ﷺ

By the time the Prophet ﷺ was sent, iqleed was well established in Arabic. In a line of pre-Islamic poetry (variously attributed to al-Abbas b. Mirdas (d. 18/639) and Al-Asha (d. 4/625)):

فتى لو ينادي الشمس ألقت قناعها … أو القمر الساري لألقى المقالدا

Had a young man sat with the sun, it would have thrown off its mask

Or the veiled moon would have committed its affairs to him

Here the phrase translated as “committed to him its affairs” is a literary metaphor that literally means “throw the keys (maqaalid).”

Likewise, Umayyah ibn Abi al-Salt, the hanif poet who died shortly before the Prophet ﷺ was sent, recited about the angels:

وحراس أبواب السموات دونه قيام لديه بالمقاليد رصد

And the guardians of the gates of the heavens below him

Stand by it with the keys (maqaaleed), watchful

The word iqleed appears in at least two hadith. One of these was collected by Bukhari, in which a companion of the Prophet ﷺ uses the word in a different plural form that in the Quranic verse:

فلما دخل الناس أغلق الباب ، ثم علق الأغاليق على وتد قال: فقمت إلى الأقاليد

When the people went inside, the gate-keeper closed the gate and hung the keys on a fixed wooden peg. I got up and took the keys (aqaaleed) and opened the gate.

The Prophet ﷺ himself used the word iqleed in the same plural form it appears in Surah az-Zumar in a hadith related by Ibn Hibban, Ahmad, and others.

أتيت بمقاليد الدنيا على فرس أبلق عليه قطيفة من سندس

Gabriel came to me on a dappled horse with the keys (maqaaleed) of the earth. Upon him was a brocade of thick silk.

According to Ibn al-Jawzi (d. 597/1201), this hadith is sahih. For more commentary on it, see Fayd al-Qadeer.

Persian origins?

Ibn Katheer (d. 774/1373) discusses the origin of iqleed in his tafsir of Surah az-Zumar:

قال مجاهد : المقاليد هي : المفاتيح بالفارسية . وكذا قال قتادة ، وابن زيد ، وسفيان ابن عيينة

Mujahid said maqaaleed means ‘keys’ in Persian. This was also the view of Qatadah, Ibn Zayd and Sufyan bin `Uyaynah.

Zamakhshari (d. 538/1144) relates that iqleed is the singular form of the word used in this verse, and says:

والكلمة أصلها فارسية. فإن قلت: ما للكتاب العربي المبين بالفارسية؟ قلت: التعريب أحالها عربية، كما أخرج الاستعمال المهمل من كونه مهملا

The word is originally Persian. And if it is said: “Why does ‘a Book in clear Arabic’ have Persian?,” I say, “Arabization renders it Arabic, just as usage takes that which is neglected out of its state of neglect.”

Likewise, Ibn Qutaybah (d. 276/889) wrote about the word maqaaleed in his work on the rare words used in the Quran:

أي مفاتيحها وخزائنها، واحدها إقليد. يقال هو فارسي معرب إكليد

It means keys or treasures, and its singular form is iqleed (إقليد). It is said: it is Persian, Arabized from ikleed (إكليد).

The word kileed (كليد), without the initial hamza, is in fact Persian for “key.” But is إقليد related to كليد, and did it enter the language of the Prophet ﷺ through Persian?

Greek origins?

Several scholars of Arabic and Islamic sciences traced the origin of the word iqleed to Latin or Greek. Al-Fayyoumi (d. 770/1368) wrote in Misbah al-Muneer:

الإقليد المفتاح لغة يمانية وقيل معرب وأصله بالرومية إقليدس

Iqleed means key in the Yemeni language, and it is originally the Roman iqleedus.

Shihab al-Din al-Khafaji (d. 1069/1659) says in his commentary on the tafsir of al-Baydawi:

وكونه معرباً أشهر وأظهر، وهو بلغة الروم إقليدس وكليد وإكليد مأخوذ منه

And the fact that it is Arabized is well-known and very clear, and it is iqleedus in the Roman language, and kileed and ikleed are taken from it.

The author of Taj al-Urus (d. 1205/1790) wrote:

وفي شرح شيخنا : وقيل لغة رومية معرب إقليدس

In our sheikh’s commentary: “It is said that it is the language of the Romans, Arabized from iqleedus.”

By “Roman” these authors meant Greek, and the ancient Greek word for “key” is in fact kleidós (κλειδός). As al-Khafaji wrote, kleidós is indeed the source of the Persian word kileed. And as I surmised back when my Quran teacher first piqued my interest in this word, kleidós is ultimately derived from an Indo-European ancestor that is also the source of the Bosnian word ključ. The English word “key,” however, is totally unrelated to kleidós.

So did iqleed enter Arabic directly from Greek, or by way of Persian, or some other way?

Himyaritic origins?

In addition to Misbah al-Muneer, several Arabic lexicons, including Lisaan al-Arab, relate the opinion that iqleed is originally from “the language of Yemen,” that is, the language of the Himyar. Many of them cite a line from a poem attributed to a pre-Islamic Himyaritic king (tubba’) on the occasion of his visit to the Kaaba:

وجعلنا لبابه إقليدا

And we made a key (or lock) for its doors

Drawing on these sources, and following a fairly exhaustive analysis, the author of Muarrab al-Quran (1998) rejects a Greek or Persian origin for iqleed and concludes that it is originally Himyaritic. He notes the poem attributed to the tubba’ of Himyar and Lisaan al-Arab’s reference to the Yemeni language, and argues that this is the most likely origin because, per the author, the root ق ل د carries diverse meanings that the Greek word kleidós does not, and vice versa.

Aramaic origins?

As-Suyuti (d. 911/1505) attributes to Ibn al-Jawzi the view that maqaaleed is originally Nabataean. The Nabataeans spoke a Western Aramaic, but Ibn al-Jawzi may have intended Eastern Aramaic. There is indeed a word in these Eastern Aramaic dialects that, like the Persian كليد, derives from the Greek κλειδός. This word is found, for example, in a Jewish Babylonian Aramaic translation (Targum) of the of book of Chronicles that is said to date to about 800 or 900 AD, about two to three centuries after the Quran was revealed. In this version, 1 Chronicles 9:27 reads:

והנון ממנן על אקלידיא למיחד ולמפתח בעדן צפר בצפר

They were appointed in charge of the keys (aqlid) for locking and opening each morning.

The word aqlid (אקליד) here is a translation of the original Hebrew mafteah (מפתח), a word of Semitic origin that is a cognate of miftah (مفتاح), the word used in Surah al-Anaam, cited above.

The word also appears in sources contemporaneous with, and centuries earlier than, the revelation of the Quran. For example, it occurs several times in the Babylonian Talmud, which was compiled from the 3rd to 6th centuries and written in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, the Eastern Aramaic dialect of the Jews. In one instance, in discussing the story of Korah (referred to as Qarun in the Quran), the keys of his treasure-house are described as a load for three hundred white mules, and “all the keys (אקלידי)(akalidei) and locks were of leather.”

An even earlier example of this word comes from the Syriac Sinaiticus, an early 4th Century translation of the Gospels into Syriac, a form of Eastern Aramaic heavily used by Christians. In this version of Matthew 23:13, Jesus addresses hypocrites:

ܘܝ ܠܟܘܢ ܕܝܢ ܣܦܪ̈ܐ ܘܦܪ̈ܝܫܐ ܢܣܒܝܢ ܒܐܦ̈ܐ ܐܚܝܕܝܢ ܐܢܬܘܢ ܐܩܠܝܕܐ ܕܡܠܟܘܬܐ ܕܫܡܝܐ ܩܕܡ ܒܢ̈ܝ ܐܢܫܐ ܠܐ ܓܝܪ ܐܢܬܘܢ ܥܠܝܢ܂ ܘܠܐ ܠܐܝܠܝܢ ܕܐܬܝܢ ܠܡܥܠ ܫܒܩܝܢܐܢܬܘܢ

You hold the key (ܐܩܠܝܕܐ) (aqlide) of the kingdom of heaven before men: for you neither enter in yourselves, nor those that are coming do you permit them to enter.

Aqlide appears several times in the Peshitta, an early Syriac translation of the New Testament, including four places in Revelation. In this version, the word does not appear in Matthew 23:13 as it does in the Syriac Sinaiticus, but Matthew 16:19 (which is lost in the Syriac Sinaiticus) has Jesus saying to Peter:

ܠܟܼ ܐܬܿܠ ܩܠܝܕܼܐ̈ ܕܡܠܟܿܘܼܬܼܐ ܕܫܡܝܐ܂ ܘܟܼܠ ܡܕܡ ܕܬܐܣܘܼܪ ܒܐܪܥܐ܂ ܢܗܘܐ ܐܣܝܪ ܒܫܡܝܐ܂ ܘܡܕܡ ܕܬܫܪܐ ܒܐܪܥܐ܂ ܢܗܘܐ ܫܪܐ ܒܫܡܝܐ

I will give you the keys (qlide) (ܩܠܝܕܐ) of the kingdom of heaven; and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you release on earth shall be released in heaven.

The word ܩܠܝܕܐ here is a translation of kleidós (κλεῖδας) in the original Greek.

The word also appears in the writing of the early Syrian church father Ephrem (d. 373 AD), wherein, for example, he describes John the Baptist as “the keeper of the keys (aqlide)(ܐܕܝܠܩܐ) of the Holy of Holies.”

The word is also used in an ancient Syriac translation of a Greek work by Evagrius Ponticus (d. 399 in Egypt), a Christian monastic theologian.

ܐܩܠܝܕܐ ܕܡܠܟܘܬܐ ܕܫܡܝܐ ܐܝܬܘܗܝ܆ ܡܘܗܒܬܐ ܕܪܘܚ܇ ܗ̇ܝ ܕܒܡ̈ܢܘܢ ܡ̈ܢܘܢ܇ ܓ̇ܠܝܐ ܣܘ̈ܟܠܐ ܕܦܘܠܚܢܐ ܘܕܟܝܢܐ܇ ܘܕܡ̈ܠܐ ܕܥܠ ܐܠܗܐ

The Key (aqlide)(ܐܕܝܠܩܐ) of the Kingdom of Heaven is the spiritual gift which partially reveals the intellections of the praktike and of the nature, and those of the logoi which concern God.

Thus, some scholars have argued that the Arabic إقليد is a loanword from Aramaic. This is the position taken by Arthur Jeffery in his Foreign Vocabulary of the Quran (1938), wherein he writes that the word:

was early recognized as a foreign word, and said by the philologers to be of Persian origin. The Pers. کلید to which they refer it is itself a borrowing from the Gk. κλείς, κλεῖδα (Vullers, Lex, ii, 876), which was also borrowed into Aram. אקליד; Syr. ܐܕܝܠܩܐ ,ܕܝܠܩܐ … In spite of Dvořak’s vigorous defence of the theory that it passed directly from Persian into Arabic, we are fairly safe in concluding that the Ar. إقليد is from the Syr. ܐܕܝܠܩܐ and the form مقلاد formed therefrom on the analogy of مفتاح, etc.

This is also the view expressed in the respected Syriac Lexicon (2009). He and Jeffery both cite Siegmund Fraenkel, whose 1866 work on Aramaic loans in classical Arabic contains an extensive discussion of the word.

Fraenkel points out that a loanword in Arabic for “key” is understandable given that in antiquity, Arabs were known for not having locks on their doors. An example he cites is Jeremiah 49:31, in which Nebuchadnezzar declares war on an Arab nation “which has neither gates nor bars, dwelling alone.” Indeed, as I noted above, the Himyarite king built the first doors for the Kaaba when he visited Mecca, and in his poem mentioned making for it an iqleed.

Fraenkel argues that “κλειδός [kleidos] by mediation of אקליד [aqlide]” must have entered Arabic at a very early period, given its use (as I noted above, in pre-Islamic poetry) in an ancient literary metaphor, with a Semitic morphology: وألقى إليه مقاليد الأمور , literally “he threw to him the keys (maqaaleed) of the affair,” i.e., he entrusted him with authority over an affair. He also states that Arabic has its own root QLD (ق ل د) that is distinct from the loanword إقليد , and he warns against presuming that the entire root is borrowed.

Given that the word’s origin in Persian or Aramaic are both authoritative, I suggest that the origin of إقليد in the Aramaic ܐܕܝܠܩܐ or אקליד rather than in Persian seems more likely because, insofar as those words begin with an aleph (א or ܐ), it would explain why إقليد begins with an alif (hamza), rather than a voweled letter as the Persian کلید does. On the other hand, the hamza would have been needed if the direct origin of إقليد were κλειδός to comply with Arabic’s rule against a word beginning with an unvoweled letter. But the likelihood of a direct borrowing from Greek into Arabic in this case also needs to be weighed against the respective historical influences of Aramaic and Greek on the language of the Arabian milieu prior to the revelation of the Quran, the former being stronger than the latter.

An Aramaic origin of إقليد would also harmonize with the fact that several classical sources posited that it was borrowed from Himyaritic and that a poem using it was attributed to a Himyarite king who visited Mecca. Yemen was ruled by a Jewish dynasty, Judaism was widespread in Yemen long before the Quran was revealed, and the Jews of Yemen were deeply familiar with Jewish Babylonian Aramaic. It would thus not be surprising for a word of Aramaic origin corresponding to إقليد to be in use among the people of Yemen.

Finally, it is perhaps significant that the Aramaic ܐܕܝܠܩܐ / אקליד and Arabic ق ل د all carry the additional meaning of neck or collarbone carried by the original Greek κλειδός, whereas I could locate no source indicating that the Persian word carries this meaning (indeed, the English word “clavicle” derives from this Greek word) . If so, then had إقليد entered Arabic by way of Persian, it would not carry the meanings of both key and neck.

The significance of the usage of إقليد in the Quran

Given that the Quran is the peak of eloquence, can we infer the wisdom and intent behind Allah’s choice of the word maqaaleed (مقاليد) in Surah az-Zumar rather than the relatively synonymous word of Arabic origin, mafaateeh (مفتاح)? Let’s first review how the Muslims understand this passage.

The author of Ruh al-Ma’ani (d. 1270/1854) wrote regarding “To Him belong the keys of the heaven and earth”:

مجاز عن كونه مالك أمره و متصرفا فيه بعلاقة اللزوم ، و يكنى به عن معنى القدرة والحفظ ، وجوز كون المعنى الأول كنائيا لكن قد اشتهر فنزل منزلة المدلول الحقيقي فكني به عن المعنى الآخر فيكون هناك كناية على كناية وقد يقتصر على المعنى الأول في الإرادة وعليه قيل هنا المعنى لا يملك أمر السماوات والأرض ولا يتمكن من التصرف فيها غيره عز وجل .

A metaphor for His being the owner of His affair, and thus the disposer thereof. And it implies the meaning of power and guardianship. And the first meaning is possible symbolically, but it became well-known and assumed the status of the literal sense, so it took on thereby the second meaning, and thus became a symbol upon a symbol. And it is limited to the first meaning in intent, and with regard to this, it is said that the meaning is, no one controls the affairs of the heavens and earth, and no one is able to direct anything in it other than Him, the Glorious and Majestic.

Prof. Emran El-Badawi, in his work The Qur’an and the Aramaic Gospel Traditions (Routledge, 2013), argues that the choice of this word is related to its usage in Aramaic in Matthew 16:19 as a metaphor for divine authority. He argues that “the use of keys as a metaphor of authority [was] established” by this Biblical verse and then “carried on in Syriac Christian literature,” from whence it “circulated in the Qur’ān’s milieu.” Thus, according to El-Badawi, the Quran “is appropriating Matthew’s notion of ‘keys to the kingdom of heaven’ but with a “stricter monotheistic” sense.

With respect to Prof. El-Badawi, it does not seem accurate or appropriate to say that Allah “appropriated” a Biblical metaphor.

Allah says in az-Zumar 39:23:

اللَّهُ نَزَّلَ أَحْسَنَ الْحَدِيثِ كِتَابًا مُّتَشَابِهًا مَّثَانِيَ

Allah has sent down the most beautiful of all teachings: a Scripture that is consistent, oft-repeated

The metaphor of keys as the symbol of power and authority was well established among the Arabs long before the Quran was revealed, as demonstrated by the fact that it had become a figure of speech, complete with the loan word iqleed, used in poetry and rhetoric by the time of the Prophet ﷺ. Had it not been so, the Quran’s reference to the keys of the heaven and earth would have been understood literally by those who first heard it. The Quran did not “appropriate” Christian scripture.

Now it is plausible that Matthew 16:19 helped to promote the intelligibility of this metaphor among the Christians of the Near East, and it may also be that, at least to some extent, it accurately represents the speech of the Prophet Jesus. If so, its similarity to the Quranic metaphor is attributable to the common source of revelation: the Lord of the Heavens and the Earth. It is also attributable to the fact that this metaphor would have been understood by the Aramaic speakers that the New Testament reached.

Moreover, because this literary metaphor was known among the Aramaic-speaking Christians and Jews of Sham, Yemen, and Medina, the Quranic language would have resonated among them as well and facilitated their responsiveness to Islam. This demonstrates the purity and effectiveness of Quranic Arabic.

Allah says:

وَمَا كَانَ هَٰذَا الْقُرْآنُ أَن يُفْتَرَىٰ مِن دُونِ اللَّهِ وَلَٰكِن تَصْدِيقَ الَّذِي بَيْنَ يَدَيْهِ وَتَفْصِيلَ الْكِتَابِ لَا رَيْبَ فِيهِ مِن رَّبِّ الْعَالَمِينَ

This Qur´an could never have been devised by any besides Allah. Rather it is confirmation of what came before it and an elucidation of the Book which contains no doubt from the Lord of all the worlds.

And Allah knows best.

وصلى الله على نبينا محمد وعلى آله وصحبه وسلم

I think you mean Qarun not Hamman (Haamaan).

LikeLike

Barakallahu feek you’re right I’ll fix it

LikeLike